A (brief) history of plants in the modern home

Posted by Jacqueline, Midrib Founder on 29th Jan 2022

House plants have featured within the modern home for centuries. The practice of bringing the outside in, although influenced by changing interior trends, has persisted.

It began with modest and practical potted plants - bought into the home both for their medicinal purposes and ability to perfume stagnant air.

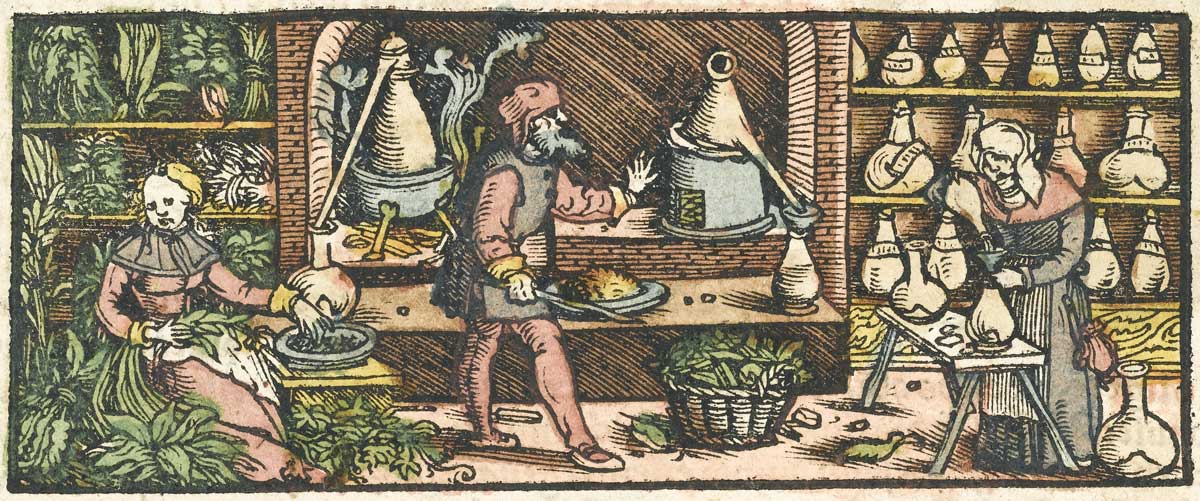

Wood cut illustrating the distilling process of essential oils using plants, c.1550. From The Wellcome Collection.

The 17th century saw arduous attempts to cultivate highly prized citrus fruits inside elaborate orangeries and glass houses. Our curiosity for plants grew into Botany, and advances within the discipline gave us the Linnean system of classification - a language to both name and identify living things*. Indoor gardening became a favoured past time, as we attempted to keep newly discovered tender plants, with varying degrees of success.

Photograph of Chatsworth House Orangerie, c.1880 from the collections of The Garden Museum

It was the Victorian era which really rooted our love affair with house plants. Embracers of ornamentation and decadent display, our great great great grandparents filled their homes with the most fashionable plant of the time: ferns. No interior was complete without bushy evergreens atop mantles, inside purposefully designed ceramics or balanced on fancy jardiniers. This fever for foliage came to be known as pteridomania, an obsession with the plant genus Pteris (a group of around 300 types of fern).

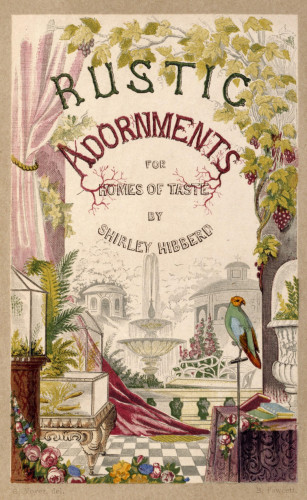

Left: Book cover: 'Rustic Adornments for Homes of Taste: and recreations for town folk in the study and imitation of nature', a book by Shirley Hibberd, published by Groombridge & Sons, London, 1856.' The illustration shows an imagined Victorian interior complete with plants, flowers and foliage-filled Wardian cases (early glass terrariums).

Below: Photograph showing the plant-filled interior of a Victorian dining room, c.1890

Both archive items are from the collections of The Museum of the Home.

The story of house plants can articulate moments in social history and interior design. Specific plants seem to encapsulate a certain look and feel. Mid-century interiors featured the ubiquitous spider plant and aspidistra. Climbers and creepers filled macramé hangers in sunken rooms of the 70s. The sunset Californian palm became a motif of the following decade, with architectural towering plants like palms and monstera invading our spaces. While the soft-focus interiors of the 90s embraced genteel, flowering plants. Sprays and sugary table arrangements complemented Laura Ashley schemes.

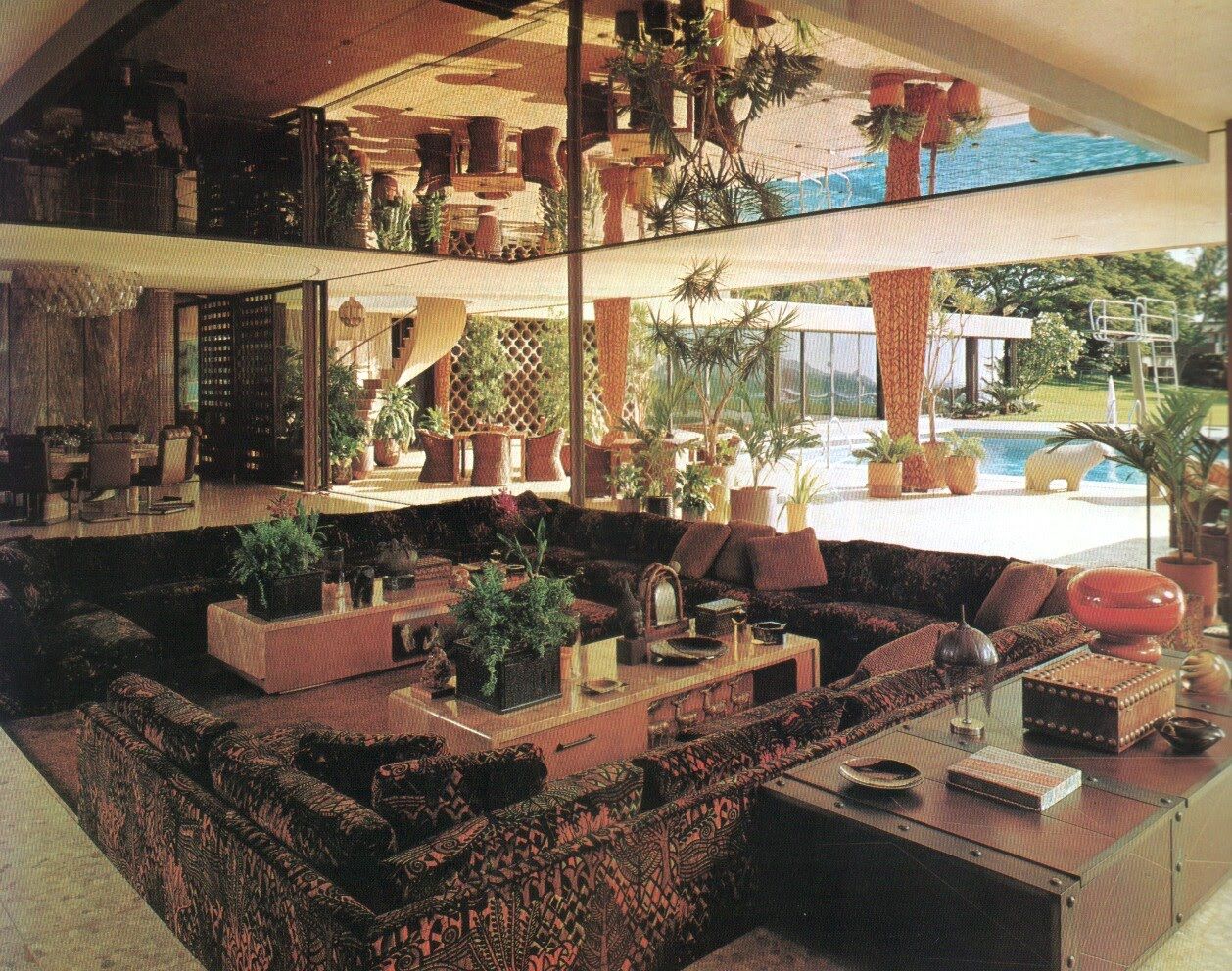

Sunken living room, c.1970 - the mirrored ceiling doubles the number of house plants. Image grabbed from Pinterest.

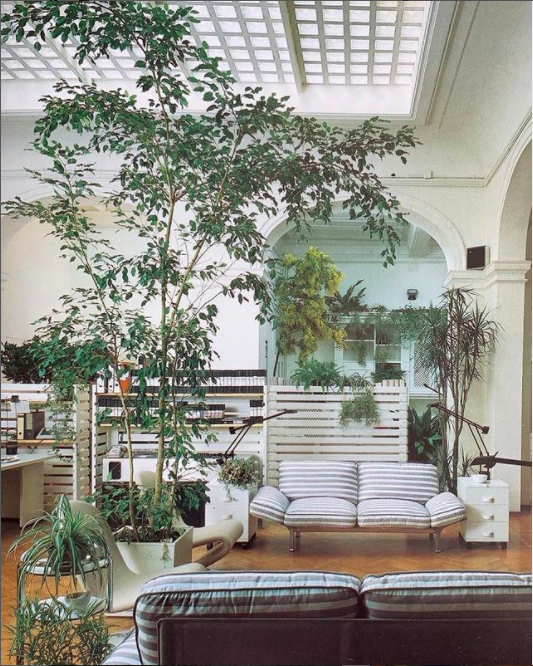

A 1980s interior filled with low-maintenance plants, including a giant ficus. Image taken from @the_80s_interior

Photograph from the Laura Ashley Book of Home Decorating showcasing a range of indoor gardening. From bountiful window boxes brimming with scent-heavy hyacinths, to baskets overflowing with candy coloured carnations.

Today, social platforms, a growing awareness of the wellbeing benefits of plants, and the impact of the pandemic have compounded to seismically increase the number of house plant enthusiasts - as well as the variety of plants available to them.

Recent and ongoing research suggests that indoor plants can offer two potential benefits – both improved mental wellbeing and better physical health. Plant care is self care, after all! The psychological benefits of plants are said to include lifting mood, reducing stress levels, aiding productivity and even increasing our pain tolerance. While the physical health benefits of keeping plants indoors are recognised as reducing blood pressure and combatting fatigue. Beyond this, plants in the home increase oxygen levels while reducing air born contaminants. Good air purifiers include Devils Ivy, Snake Plants, English Ivy, ZZ plants, Calathea, Rubber Plants and Dracaena (among others).You can check Midrib's collection of air purifying plants here.

The healing power of plants, Fran Bailey. One of a number of books exploring the benefits of house plants.

In a social, post-pandemic future Biophilic Design is influencing the way we live. In other words, a desire for increased connectivity to nature is shaping the design of our homes, and by association - our behaviour. Home improvement, being one of the few activities permitted during the national lockdowns, became the focus of many. The care and maintenance of plants can be seen as a natural extension to this. We embraced house plants like never before and turned our living rooms into jungles. We just as eagerly retrofitted living spaces into our gardens so that Covid-permitted social contact could take place. Literally transplanting the home into the garden.

One of many articles investigating the impact of Covid-19 on our relationship to gardening - indoors and out. You can read the Financial Times article here.

And perhaps at the other end of the spectrum - this appetite for greenery has created micro-networks of grower-to-customer relationships (maintained primarily via Instagram), catering to those seeking rare and often eye-wateringly expensive plants. Cuttings can be propagated and sold, enabling both rivalry and appreciation between house plant collectors.

Our relationship with house plants remains fertile. Next time you water your pot plant, know that you and it are part of a long lineage!

*A critical note for the reader

The European botanist Carl Linneaus created binomial nomenclature (naming). This is the accepted and prevalent system of naming and identifying plants today. It uses two names, the first to describe genus and the second to signify species. For example, Monstera deliciosa. It's important to recognise that the story of Botany often hides a colonial past which is perpetuated within horticulture.

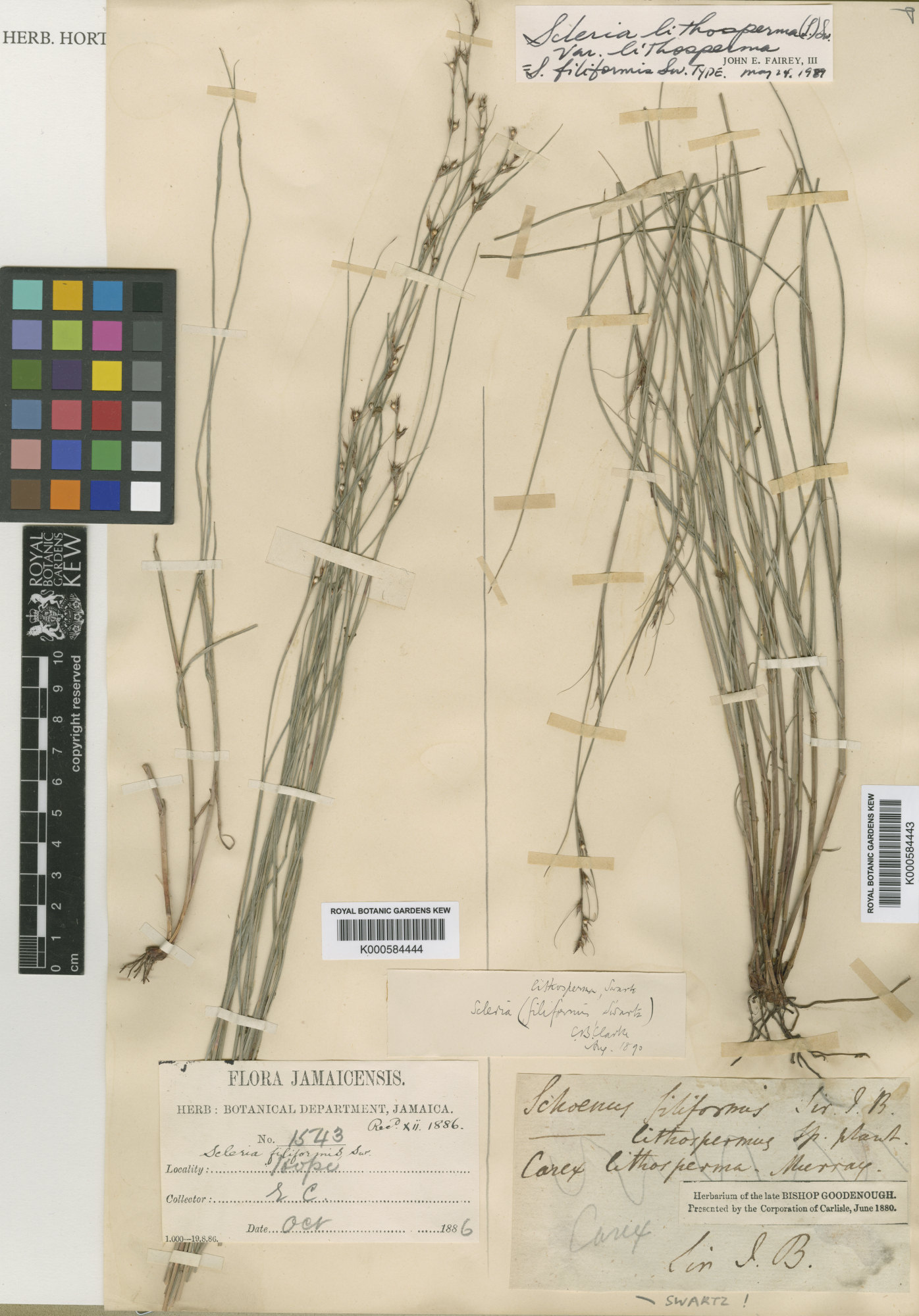

Sheet specimen collected by J Banks in Jamaica, c.1890. From the Herbaria collections of the Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew.

The use of such scientific language is just one of the ways this is achieved. It erases the histories and knowledge associated with First Nations people - from countries in which the plants first originated. This is a complex issue which is increasingly recognised and discussed.

Similarly, the history of Botany (along with other progressive disciplines) is interwoven with the expansion of empire. Western individuals set out to 'discover' economic crops and never-before-seen specimens. This period of intercontinental travel exploited existing commercial networks, many of which were slave trade routes. It's also worth saying that the passion for collecting and preserving plants within European institutions, and their subsequent availability/consumption in the marketplace has had a detrimental impact on speciecs numbers and habitats.

If you're interested in learning more, @decolonisethegarden is a platform that brings an antiracism, equality and justice lens to gardening.